Don’t want the in depth guide? Check out the quick break down here

Block Cipher Modes of Operation Explained: ECB vs CBC vs CTR vs GCM (CISSP Guide)

Block cipher modes of operation define how a block cipher repeatedly transforms chunks of data to achieve secure encryption beyond a single block. A block cipher alone (like AES or DES) only encrypts a fixed-size block (e.g. 128 bits for AES), so modes of operation describe how to apply the cipher to larger messages securely[1]. Each mode has distinct characteristics, use-cases, and security implications. This guide progresses from basic to advanced modes – ECB, CBC, CTR, and GCM – explaining how they work, how to implement them correctly (key management, IV/nonce usage), their vulnerabilities (e.g. padding oracles, IV reuse, known-plaintext attacks), and relevant standards (NIST, ISO, FIPS) that govern their use. We’ll also briefly mention newer modes like OCB and ChaCha20-Poly1305 and their relevance to the CISSP exam. The goal is to equip CISSP candidates with both conceptual understanding and practical security insights for these encryption modes.

Understanding Block Cipher Modes and Standards

Modern cryptography standards define several modes of operation to meet security goals like confidentiality and authenticity The earliest modes – ECB, CBC, CFB, OFB – were introduced in 1981 with the DES cipher (FIPS PUB 81). NIST’s Special Publication 800-38A (2001) updated these for AES and added CTR (Counter Mode). Later, modes providing authenticated encryption (combining encryption and integrity) were standardized (e.g. GCM in NIST SP 800-38D, 2007). International standards like ISO/IEC 10116 also define ECB, CBC, CFB, OFB, and CTR modes for block ciphers. These standards emphasize crucial implementation requirements – especially regarding initialization vectors (IVs) or nonces – to ensure security. In general, most modes require a unique, non-repeating IV/nonce for each encryption under a given key. Reusing an IV or counter can catastrophically undermine confidentiality, as we will discuss for specific modes. The sections below delve into each mode in detail.

Electronic Codebook (ECB) Mode

Overview: Electronic Codebook (ECB) is the simplest block cipher mode. In ECB, the plaintext is divided into blocks (e.g. 128-bit blocks for AES), and the cipher encrypts each block independently with the same key. There is no chaining or feedback between blocks. The encryption of block Pᵢ is simply Cᵢ = E_K(Pᵢ), and decryption Pᵢ = D_K(Cᵢ), for each block. Because of its simplicity, ECB has low overhead and allows random access to encrypted blocks. It does not require an IV.

Practical Use and Key Management: In practice, ECB is not recommended for encrypting sensitive data. Its only redeeming quality is simplicity – there’s no IV to manage and no dependency between blocks, so encryption can be parallelized and is straightforward. However, the lack of an IV means ECB produces identical ciphertext for identical plaintext blocks under the same key. This makes key management in ECB no different than managing the raw block cipher key – the key must be kept secret and strong, but ECB offers no additional mechanism (like an IV/nonce) to randomize encryption. If used at all, ECB might be found in niche cases such as encrypting a single fixed-size block (e.g. a random key or hash value), or in certain database encryption where each field is independently encrypted. Even then, security professionals are advised to avoid ECB for any scenario where patterns in data matter, because of the vulnerability described next.

Vulnerabilities: The glaring weakness of ECB is its deterministic, block-by-block nature. Identical plaintext blocks encrypt to identical ciphertext blocks, leaking patterns in the data. An observer who intercepts ECB-encrypted data can recognize repeated patterns or predict structure if any plaintext structure is known. A classic example is encrypting an image with ECB – the famous “ECB penguin” demonstrates that large areas of uniform color in the plaintext result in repeating ciphertext blocks that still reveal the original image’s outline. Below, the image on the right shows the Linux Tux mascot encrypted in ECB mode – one can clearly discern the shape of the penguin because ECB did not hide the repeated background pattern.

An image encrypted with AES-ECB still shows visible structure, as identical plaintext blocks produce identical ciphertext blocks. In this example, the outline of the Tux penguin remains evident, illustrating why ECB is not semantically secure for general data.

This lack of diffusion violates modern security goals (ECB is not semantically secure), making it trivial for attackers to perform known-plaintext analysis or even simple pattern matching. For example, if an attacker knows that a certain plaintext block (e.g. “PAYMENT APPROVED”) appears somewhere, they can search for its ciphertext pattern in any ECB-encrypted message to locate it. Furthermore, without an integrity mechanism, ECB ciphertext blocks can be cut-and-pasted or replayed by an attacker. Since each block is independently encrypted, an adversary could replay blocks (reordering or duplicating encrypted blocks) and the decrypted result will still be meaningful, which can facilitate replay attacks.

Because of these issues, ECB is considered fundamentally insecure for most uses. In fact, NIST’s vulnerability database classifies use of ECB on confidential data as a severe security vulnerability. Current NIST guidance proposes disallowing ECB except in very limited cases explicitly permitted by other standards. CISSP Tip: On the exam, ECB is often cited as the incorrect choice – a textbook example of a weak mode. Remember that ECB “encrypts in place” without randomization, causing pattern leakage. It should not be used for encrypting passwords, messages, files, or any repetitive data; it’s mainly a foil to illustrate what not to do.

Relevant Standards: ECB is defined in all major standards (FIPS 81, NIST SP 800-38A, ISO/IEC 10116) as a valid mode, but with warnings. NIST SP 800-38A notes that if the property of identical plaintext yielding identical ciphertext “is undesirable in a particular application, the ECB mode should not be used.” In modern practice, ECB is largely deprecated. For FIPS-validated cryptographic modules (FIPS 140-3), AES-ECB might be allowed only for specific non-data use cases (like encrypting other keys or random paddings), but not for general data encryption due to its vulnerabilities. Both NIST and ISO standards encourage using a mode that incorporates an IV or other randomness for any multi-block data.

Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) Mode

Overview: Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) was one of the earliest improvements over ECB. In CBC mode, each plaintext block is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before encryption, creating a chain of dependency. This means each ciphertext block depends on all prior plaintext blocks, greatly increasing diffusion.

Note: Here’s what each symbol represents:

- Pⱼ → Plaintext block number j

- Cⱼ → Ciphertext block number j

- EK( ) → Encrypt using secret key K

- DK( ) → Decrypt using secret key K

- ⊕ → XOR (bitwise exclusive OR)

- IV → Initialization Vector (random, one block in size)

- The IV is not secret. Its job is to make sure the first block doesn’t behave like ECB.

Formally, for block P₁, C₁ = E_K(P₁ ⊕ IV) (where IV is an initialization vector); for subsequent blocks P₂…P_n, Cⱼ = E_K(Pⱼ ⊕ C_{j-1}). For decryption, P₁ = D_K(C₁) ⊕ IV and Pⱼ = D_K(Cⱼ) ⊕ C_{j-1}. The IV is a random bitstring of one block length that starts the chaining. By XORing plaintext with the previous ciphertext, identical plaintext blocks yield different ciphertexts depending on context, overcoming ECB’s primary flaw.

IV Usage and Requirements: CBC requires a fresh IV for each encryption session (each message encrypted). The IV need not be secret, but must be unpredictable/random for security. According to NIST, the IV should be statistically unique and unpredictable to ensure the first block’s encryption is randomized. In practice, IVs are often generated via a secure random generator and transmitted alongside the ciphertext (often prepended). Critically, an IV should never be reused with the same key, because if two messages share an IV under the same key, then their first ciphertext blocks would be encryptions of identical plaintext XOR that IV, revealing the XOR of the two messages’ first blocks. (More formally, C₁ = E_K(P₁ ⊕ IV), so if IV is reused, an attacker given C₁ from two messages can XOR them to cancel out E_K(·) and derive P₁^(1) ⊕ P₁^(2).) Fortunately, generating a random 128-bit IV makes collisions extremely unlikely if done correctly. CBC also requires padding of the final plaintext block (e.g. using PKCS#7 padding) if data isn’t a multiple of the block size, since it operates on whole blocks.

Practical Implementation: CBC was the workhorse mode for many years – used in protocols like TLS 1.0–1.2, IPSec, older file encryption utilities, etc. It offers good confidentiality if implemented properly, but does not provide integrity/authenticity on its own. A common implementation strategy is encrypt-then-MAC: use CBC for encryption and then append a message authentication code (MAC) to detect tampering. Key management for CBC involves distributing the symmetric key securely and ensuring each encryption uses a new IV. Many protocols simply include the IV in plaintext with the ciphertext (since IV isn’t secret), or derive the IV from a random per-message value. The integrity of the IV should be protected in transit – if an attacker could tamper with the IV, they can manipulate the decryption of the first block (since P₁ = D_K(C₁) ⊕ IV, flipping bits in IV flips bits in recovered P₁). Thus, in practice, the IV might be sent alongside data but the entire package (IV + ciphertext) should be covered by an integrity check or an authenticated mode.

Security Strengths: CBC’s chaining achieves semantic security (distinct ciphertext for repeated blocks) as long as the IV is unpredictable. It also has a self-healing property: a random bit error in one ciphertext block will corrupt that block’s plaintext upon decryption and partially affect the next block, but does not propagate further. Specifically, a 1-bit change in ciphertext Cⱼ causes the decryption of Pⱼ to be completely garbled, and flips the corresponding bit of P_{j+1}, but P_{j+2} and onwards decrypt correctly. This is an improvement for random error tolerance compared to modes like OFB (where bit errors don’t propagate at all) or ECB (where each block decrypts independently). However, it also means malleability: an attacker can tweak bits in ciphertext Cⱼ, causing predictable changes in plaintext P_{j+1} (and random corruption in Pⱼ). This malleability can be exploited unless we have an integrity check.

Vulnerabilities: The primary vulnerabilities in CBC arise from IV misuse and padding/oracle issues:

- IV Predictability/Reuse: If the IV is not truly random or is reused, CBC can be attacked. A notable example is the BEAST attack (CVE-2011-3389) on TLS 1.0, where the way IVs were chosen (using the last ciphertext block of the previous record) allowed an attacker to predict the IV for the next TLS record. This enabled a chosen-plaintext attack to gradually decrypt secure cookies. NIST explicitly cites incorrect IV generation as a source of practical vulnerabilities like the BEAST attack. The lesson: Never reuse an IV under a given key, and ensure IVs are random/unpredictable. Reuse breaks the chaining randomness and can expose relationships between messages.

- Padding Oracle Attacks: CBC requires padding the final block. If a system decrypts a CBC ciphertext and then checks padding bytes, any difference in error behavior (e.g. a “padding invalid” message) can act as a side-channel (an oracle) for attackers. In the famous Vaudenay’s padding oracle attack (2002), an attacker who can feed chosen ciphertexts to a system and observe whether padding errors occur can incrementally recover the plaintext. This attack and its variants were used against web frameworks (e.g. an old ASP.NET vulnerability) to decrypt cookies, and even against TLS (the POODLE attack on SSL 3.0 exploited CBC padding specifics). Essentially, by tweaking a ciphertext block and observing if the padding is valid, attackers learn information about plaintext bytes. Real-world impact: Padding oracle flaws have been repeatedly found in improperly designed encryption APIs and protocols, underscoring that CBC alone provides no authentication – a separate integrity check or an authenticated mode is needed to prevent such attacks. Modern TLS versions (1.3) dropped CBC entirely in favor of AEAD modes to avoid these pitfalls.

- Malleability and Bit-Flipping: As mentioned, an adversary can flip specific bits in the ciphertext to produce controlled changes in the decrypted plaintext. For example, in ciphertext block C₂, flipping a particular bit will flip the same bit in plaintext P₃ (while completely garbling P₂). This could be used maliciously (e.g. to manipulate some plaintext fields if their position is known), unless a MAC or authentication is used. Researchers even demonstrated CBC malleability for code injection: Fujita et al. (2021) showed how modifying bits in CBC-encrypted binary files could introduce exploits. Thus, without integrity, CBC-encrypted data can’t guarantee authenticity.

Despite these issues, CBC can be safe if implemented with care: use random IVs, never reuse IVs, always use an integrity check (e.g. HMAC) or switch to an authenticated mode. Many legacy systems still use CBC, so CISSP candidates should know its proper use and dangers.

Key points: CBC hides patterns (unlike ECB) but is vulnerable to IV management errors and padding oracles. It’s a confidentiality-only mode, so pairing with a MAC or moving to authenticated encryption is now recommended.

Relevant Standards: CBC is included in FIPS 81 and NIST SP 800-38A as a recommended mode of operation. NIST SP 800-38A mandates an unpredictable IV for CBC and even provides an Appendix on generating IVs securely ISO/IEC 10116 also specifies CBC and its properties. U.S. government standards (like NIST SP 800-38F for AES key wrapping, etc.) historically allowed CBC in various protocols, but current guidance is moving away from unauthenticated CBC. Notably, as of 2022 NIST plans to disallow pure CBC (and other non-authenticated modes) in future protocols unless mitigating controls are in place. The trend in standards is toward modes like GCM or CCM (which combine CBC’s confidentiality with a MAC) to avoid the outlined vulnerabilities. That said, CBC remains a valid mode in exams and practice – just remember its needs (random IV, padding) and weaknesses (padding oracle, malleability). It often appears in exam questions as a contrast to ECB or as an example of a mode requiring IV management.

Counter (CTR) Mode

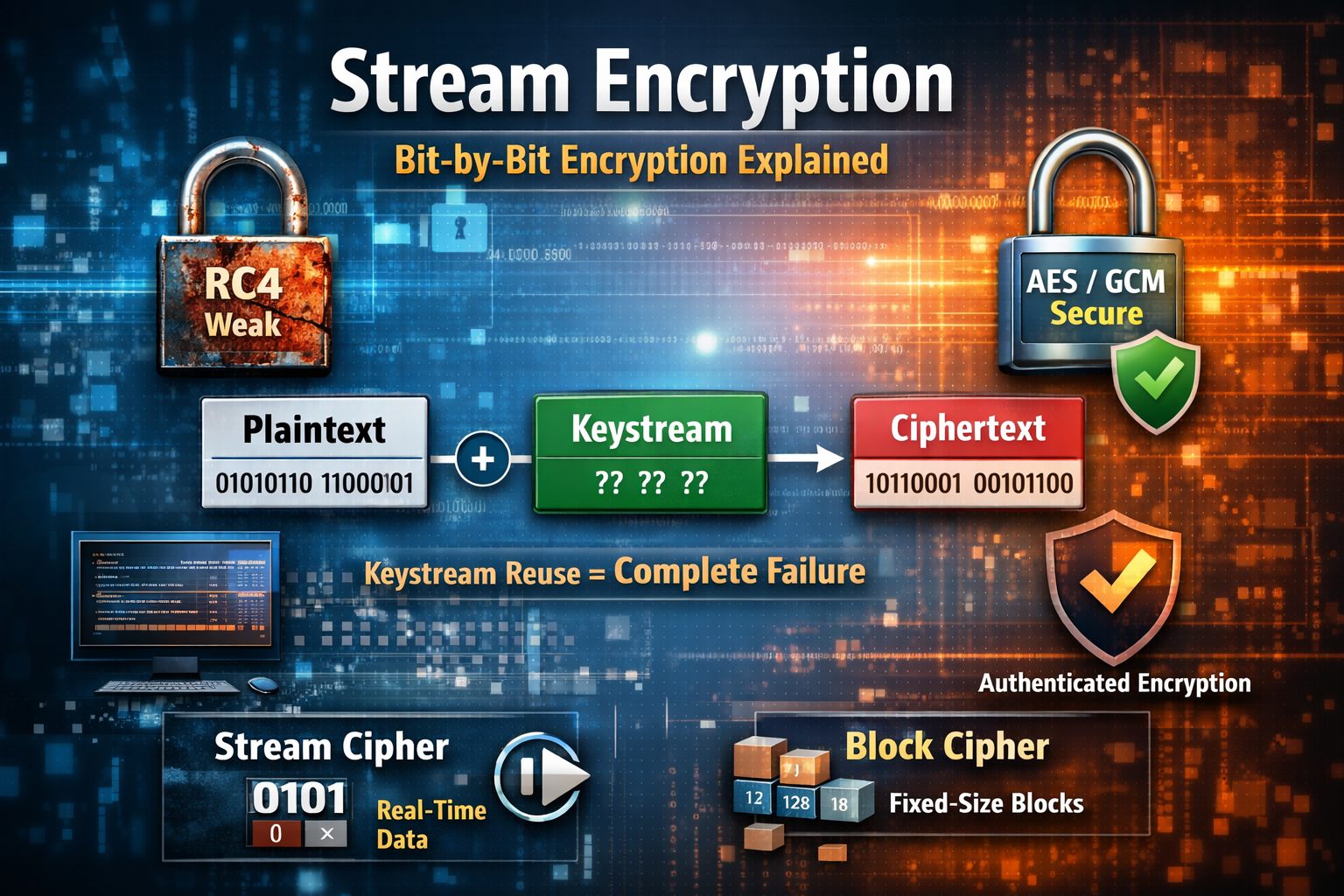

Overview: Counter (CTR) mode transforms a block cipher into a stream cipher. Instead of chaining ciphertext blocks, CTR mode generates a keystream by encrypting successive counter values and XORing them with the plaintext.

In CTR, we choose a unique nonce (IV) and an initial counter value, then for block j: Oⱼ = E_K(Tⱼ), and Cⱼ = Pⱼ ⊕ Oⱼ. Here Tⱼ is the j-th counter block in a sequence (e.g. an incrementing integer, or some combination of nonce and counter). Decryption is the same process: generate the same keystream Oⱼ and XOR with Cⱼ to recover Pⱼ. The crucial security requirement is that each counter block value must be unique across all encryptions with the same key**. If the counter never repeats, CTR mode achieves security equivalent to a one-time pad (with a pseudorandom keystream).

How CTR Works: Typically, CTR concatenates a nonce and a block counter to form the input Tⱼ to the cipher. For example, a 128-bit counter block might use 64 bits of a nonce and 64 bits for an integer count. For the first block, the counter might be nonce || 0, then nonce || 1, and so on. The cipher E_K encrypts each counter block to produce a pseudorandom output, which is XORed with plaintext. Because each counter block is different, the keystream for each block is different. Importantly, encryption and decryption are identical operations (just XORing the keystream), and blocks can be processed in parallel since counter values can be generated independently. This makes CTR highly efficient on multi-core or hardware implementations. CTR also doesn’t require padding; you can encrypt partial blocks by XORing the needed portion of keystream and discarding the rest.

Nonce/IV Management: CTR’s security hinges on the uniqueness of the IV/counter sequence for each key. The nonce (IV) in CTR mode is often a random or semi-random value chosen for the message, combined with a counter that starts at 0 (or another start) and increments. It’s acceptable to use a simple incremental counter as long as the starting nonce is unique for each encryption session. NIST SP 800-38A specifies that “across all of the messages that are encrypted under the given key, all of the counters must be distinct.” If this condition is violated (i.e., a counter value repeats with the same key), two different plaintexts will be XORed with the same keystream block Oⱼ, and thus their XOR will be exposed: Cⱼ^(1) ⊕ Cⱼ^(2) = Pⱼ^(1) ⊕ Pⱼ^(2). This is the classic two-time pad problem – if an attacker knows or can guess one of the plaintexts, they can recover the other; even if not, redundancy in plaintexts can often be exploited. In sum: CTR absolutely breaks if a (key, nonce) pair is ever reused.

Practically, implementers often use a 96-bit or 128-bit nonce for CTR. For example, IPsec might use the packet IV as part of the counter. One common approach is to use a random 64-bit nonce and a 64-bit counter. Alternatively, the nonce could be a message sequence number. If the nonce is random, one must be mindful of the birthday paradox if encrypting enormous volumes (e.g. with 64-bit random nonces, collisions become likely after 2^32 messages; NIST sometimes gives guidance to limit uses under one key to mitigate any collision probability). If the nonce is a simple counter (starting at 0 for the first message and incrementing for each new message), one must ensure it never resets for that key. In hardware contexts (like disk encryption), XTS mode (a tweak of CTR) is often used to incorporate sector indices as part of the counter to avoid reuse.

Strengths and Uses: CTR mode has several advantages: – Parallelizable: Each counter encryption E_K(Tⱼ) is independent, so CTR can fully leverage parallel processing or pipeline architectures. This makes it extremely fast on modern CPUs (and amenable to hardware acceleration). – Random Access: Since CTR is like a stream cipher, you can decrypt/encrypt at an arbitrary block if you know the counter for that position. This means you can seek into the middle of an encrypted file and decrypt that portion without processing earlier blocks (useful for certain storage encryption scenarios). – No Padding Overhead: CTR effectively turns the block cipher into a stream cipher, so you encrypt exactly the plaintext length (except possibly a partial last block which is handled by truncating the keystream. There’s no need for padding bytes and no risk of padding oracle issues. – Simplicity of Decryption: Decryption is identical to encryption (just generating the same keystream and XORing), simplifying implementation and reducing the chance of separate encryption vs decryption bugs.

Given these, CTR is widely used in high-performance applications. It’s often seen in combination with an authentication mechanism. For instance, the widely used GCM mode (next section) uses CTR for encryption combined with a Galois-field hash for authentication. Another variant, CCM (Counter with CBC-MAC), uses CTR for encryption and a CBC-MAC for authenticity (used in wireless security standards). Even when not using an AEAD, one might pair CTR with a separate HMAC for integrity.

Vulnerabilities: CTR’s big caveat is IV/nonce reuse. Using the same IV (nonce) twice with the same key in CTR results in keystream reuse, which leads to immediate information leakage. To highlight: if two ciphertexts $C^{(1)} = P^{(1)} \oplus \text{keystream}$ and $C^{(2)} = P^{(2)} \oplus \text{keystream}$ were produced with the same keystream, then $C^{(1)} \oplus C^{(2)} = P^{(1)} \oplus P^{(2)}$. This XOR of plaintexts might be enough to recover both, especially if one is known or has predictable structure (known-plaintext attack). This scenario occurred famously in the context of the old WEP wireless protocol (which wasn’t CTR but a stream cipher with a short IV – IVs repeated frequently, allowing attackers to recover keystreams). In modern times, any system that mistakenly repeats a nonce in CTR or GCM becomes vulnerable. For example, consider an implementation bug that always sets a nonce to 0 – all messages encrypted with the same key would reuse the counter sequence starting from 0, leaking plaintext relationships. There have been real CVEs: one case is a vulnerability in some network devices where an improper random number generator caused IV collisions in AES-CTR/GCM, allowing attackers to recover data. (E.g., CVE-2017-5933 detailed a bug where a Citrix appliance “randomly” generated GCM nonces but occasionally reused them, letting attackers forge and decrypt data – the same concept applies to CTR mode.) The bottom line: reusing a CTR nonce is as bad as reusing a one-time pad key – it blows secrecy completely.

Another consideration: CTR by itself provides no authentication. It is susceptible to bit-flipping attacks just like any stream cipher. If an attacker flips a bit in the ciphertext, that bit will flip in the decrypted plaintext, with no way for the decryptor to detect it (unless an external integrity check is used). For example, if a hacker knows a portion of plaintext is an amount $=100.00$, they could flip bits in the ciphertext to change it to, say, $=900.00$, and the system would decrypt the modified ciphertext to the tampered plaintext. Thus, like CBC, CTR is malleable and must be combined with a MAC or used in an AEAD mode to guarantee integrity.

Relevant Standards: CTR was standardized by NIST in SP 800-38A (2001) as an approved mode for confidentiality[5]. NIST’s recommendation is clear that counters must be unique across all messages under one key. The standard even provides example methods (e.g., concatenating a nonce and a counter field) and warns against simplistic reuse or combination that could allow an attacker to control counter values. ISO/IEC 10116 also includes CTR (sometimes called Segment Integer Counter Mode, SIC). In practice, CTR is FIPS-approved and often the basis for AEAD schemes. CISSP exam-wise, CTR mode may be presented as a modern alternative to CBC that offers parallelism and no pattern leakage, with the trade-off that careful nonce management is required. Remember that “CTR = counter mode = turns block cipher into a stream cipher,” and unique nonce per encryption is mandatory. Also recall that CTR is one of the two modes (along with CBC) highly recommended by some experts for software implementations – Ferguson and Schneier, for example, praise CTR for its simplicity and performance – but always with the caveat of using it in conjunction with a message authentication method.

Galois/Counter Mode (GCM)

Overview: Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) is a widely adopted authenticated encryption mode that combines the ideas of Counter mode for encryption with a Galois-field (GF) hash for authentication. GCM provides confidentiality andintegrity in one symmetric algorithm, making it an AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) scheme. It is built on top of CTR mode encryption – it uses AES (or another block cipher) in counter mode to encrypt plaintext – and simultaneously computes an authentication tag (using a polynomial multiplication in GF(2^128) over the ciphertext and any additional authenticated data). The result is a ciphertext + 128-bit tag that assures the data has not been tampered with. GCM’s design goals include high throughput with low overhead, especially by leveraging parallelism and pipelining (which CTR provides).

How GCM Works: GCM takes a key, a nonce/IV, plaintext, and optional additional authenticated data (AAD) as input. Encryption in GCM proceeds like regular CTR mode: a 96-bit IV (nonce) plus a counter (starting at a specified value, typically 1) are encrypted to produce keystream blocks, which are XORed with plaintext blocks to get ciphertext. Simultaneously, the ciphertext blocks (and AAD, if any) are fed into a Galois-field multiplication operation to compute an authentication tag. In simplified terms, GCM treats the ciphertext as coefficients of a polynomial and multiplies by a hash subkey H (which is E_K(0), the cipher’s output on an all-zero block) in GF(2^128) to produce a tag. The result is a 128-bit tag (or a truncated version) that is appended to the ciphertext. On decryption, the recipient recomputes the tag and verifies it to ensure both confidentiality and integrity.

IV/Nonce Requirements: GCM, like CTR, absolutely requires a unique IV for every encryption with the same key. This cannot be overstated: if an IV is ever reused in GCM, not only is confidentiality lost (as with CTR), but integrity is also broken – an attacker can potentially recover the XOR of plaintexts and also forge messages without the key. The security “blows up” on IV reuse. NIST SP 800-38D (which specifies GCM) mandates that the probability of IV collision should be very low, e.g. < 2^-32 over the lifetime of the key. The standard recommends using a 96-bit IV, because GCM has an optimized process for 96-bit nonces (no need for additional hashing of the IV) and it simplifies compliance with the uniqueness requirement by providing a large space. Many implementations use a fixed IV portion per key (e.g. derived from a key identifier) and a counter for each message, or simply random 96-bit nonces tracked to avoid repeats. Implementers should be cautious: some libraries do not enforce IV uniqueness (e.g. they might accept a user-specified IV without checking), so the responsibility is on the developer to ensure each IV+key combination is one-time. A common practice is to combine a stable nonce (like packet or message sequence) with a random component to get a 96-bit IV that won’t repeat.

Practical Use: GCM is extremely popular in modern protocols and standards because it is fast and provides authenticated encryption in one pass. For example: – TLS 1.2 and 1.3 cipher suites heavily use AES-GCM (e.g. TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256). – IPsec (ESP) has AES-GCM as an option, combining encryption and integrity without needing a separate HMAC. – Secure storage and file encryption tools also adopt GCM for its efficiency on platforms with AES hardware acceleration.

Performance-wise, GCM can encrypt and authenticate at speeds close to plain AES encryption, especially if using CPU instructions for carry-less multiplication (for the Galois hash). It’s designed for parallelism: encryption is CTR (parallelizable), and the GHASH (Galois hash) can also be parallelized or pipelined.

Security Benefits: GCM’s security (when used properly) is twofold: – Confidentiality: Provided by AES-CTR, which is secure under the condition of unique IV. – Integrity/Authentication: Provided by the Galois field tag. The tag will detect any modification to ciphertext or the associated data. Without the correct tag, decryption will fail verification with overwhelming probability (for a 128-bit tag, an attacker’s chance of a random successful forgery is 1 in 2^128 if the key is unknown). – Associated Data: GCM can authenticate AAD (headers or other metadata that is not encrypted but must be integrity-protected). This is useful in networking (e.g. not encrypting packet headers but still ensuring they aren’t altered).

Vulnerabilities: The primary pitfalls of GCM arise from misuse, not weaknesses in the algorithm: – IV/Nonce Reuse: As stressed, reusing an IV with GCM is catastrophic. It not only leaks information as in CTR, but also allows for trivial forgeries. If an attacker ever observes two different ciphertexts with the same key and IV, they can XOR them to cancel the keystream and obtain XOR of plaintexts, and moreover, using properties of GHASH, they could forge a valid tag for a modified ciphertext (this scenario is known as the “nonce-disrespecting adversary” case in research). Real-world incidents (like the aforementioned CVE-2017-5933 with Citrix, or issues in some Java libraries around 2016) underscore that IV mismanagement immediately undermines GCM. Developers must ensure uniqueness, either by using a strictly monotonic counter for IVs or a cryptographically secure random with negligible collision probability.

– Short Tags: GCM allows tags shorter than 128 bits, but using very short tags (e.g. 32 or 64 bits) weakens security against brute-force forgery. NIST requires at least 96-bit tags in some contexts to be considered safe. Truncating the tag reduces the attacker’s work to guess a valid tag (e.g. a 32-bit tag gives 1 in 2^32 chance to succeed by chance, which might be unacceptable).

– Timing Side-Channels: The Galois field multiplication in GHASH is a fixed operation, but older GCM implementations could be vulnerable to timing attacks if not using constant-time arithmetic (particularly if using big integer libraries). However, most modern implementations use hardware (like the PCLMULQDQ instruction on x86) or well-timed loops, so this is less of an issue in practice. Still, a CISSP might not need this level of detail – just be aware that any crypto mode could have side-channel issues if implemented naively.

– Weak Keys: In theory, AES-GCM doesn’t have the class of weak keys that some older modes (like certain CBC-MAC or stream ciphers) might have. The only thing akin to a concern is that the GHASH subkey H = E_K(0) could be all-zero with extremely low probability (for a random key, the probability that AES_K(0) = 0 is $2^{-128}$, essentially impossible). If that happened, the authentication would degenerate (tag would not depend on ciphertext), but this is not a practical concern.

When GCM failures happen, they are almost always due to violating the usage guidelines. For example, a developer might mistakenly use a fixed IV for all messages (thinking it’s like CBC where IV can be public – but if it’s fixed, that’s IV reuse!). Or generating IVs with a poor random generator leading to duplicates. Another example: some encryption libraries require the caller to manage the nonce counter externally – if the caller doesn’t, they might reuse the same IV without realizing. Standards like NIST SP 800-38D heavily emphasize IV management to prevent these mistakes.

In summary, AES-GCM is very secure and efficient when used correctly, and it has become a gold standard for authenticated encryption. Its vulnerabilities surface only if implementers violate the unique-IV rule or choose insecure parameters. As a CISSP, remember that GCM is an AEAD mode combining CTR for encryption and a Galois hash for authentication. It’s favored in modern protocols (so it’s very relevant to real-world security), and you should know that it protects against the attacks that plague CBC (padding oracles, etc.) by providing built-in integrity. However, GCM shares CTR’s sensitivity to IV reuse, so key/IV management is still paramount.

Relevant Standards and Guidelines: GCM is specified by NIST SP 800-38D. This standard requires unique IVs and even provides guidance on the maximum number of invocations per key to keep collision probability low. NIST recommends 96-bit IVs and discusses how to construct IVs (random or via a deterministic counter). GCM (with AES) is FIPS-approved for use in government systems, and FIPS 140-3 modules often list AES-GCM among approved algorithms. IETF RFCs (like RFC 5288 for TLS 1.2, RFC 7518 for JSON Web Encryption, etc.) mandate AES-GCM for various secure protocols, always with the caveat “the nonce value MUST be unique for each key”. In the ISO/IEC world, GCM is also recognized (it may be referenced in ISO 19772 or others as an AE mode).

For the CISSP exam, it’s important to recognize GCM as a modern, recommended mode that provides both encryption and authentication. It might be referenced in questions about secure protocol design (e.g. “which mode would provide both confidentiality and integrity for data in transit – ECB, CBC, or GCM?” Answer: GCM). Also, an exam might test understanding that using GCM prevents the need for a separate MAC (unlike CBC+HMAC) and avoids issues like padding oracles. Just be aware of the IV uniqueness requirement as a potential exam nuance (e.g. a question might describe a scenario of reused nonces leading to failure).

Newer Modes and Algorithms: OCB and ChaCha20-Poly1305

Beyond the classic modes above, there are newer or more specialized modes of operation and algorithms. Two notable examples are OCB mode and ChaCha20-Poly1305. While these are less likely to be deeply tested on the CISSP exam, it’s worth knowing what they are and their general significance:

- OCB (Offset Codebook Mode): OCB is an authenticated encryption mode (like GCM) that was designed to be extremely efficient – it encrypts and authenticates in one pass with minimal overhead. It uses a technique of offsetting the plaintext blocks (XORing with masks derived from a nonce) before encrypting with ECB internally, and produces a tag similar to a MAC. OCB is “single-pass” (as opposed to older two-pass modes like CCM which do encryption and MAC separately)[59]. Its performance is excellent; in fact, OCB is one of the fastest AEAD modes known, often outperforming GCM at equivalent security. Why isn’t it widely used? Mainly due to patent issues: OCB was patented, and until recently, using it in many products required a license. This hampered its adoption compared to GCM (which was unencumbered and promoted by NIST). The patent has since been waived or expired for many cases (as of the mid-2020s), so we might see more of OCB in the future. It is standardized in some places (IETF RFC 7253 defines OCB for IPsec and TLS). However, for CISSP purposes, OCB is not a focus – you should simply recognize it as another AEAD mode providing confidentiality and integrity. The exam is more likely to mention mainstream modes (CBC, GCM) unless in a very forward-looking question. So know that OCB = authenticated encryption mode, very fast, but was patent-restricted and thus less common.

- ChaCha20-Poly1305: This is actually not a block cipher mode, but a combined algorithm that has become prominent. ChaCha20-Poly1305 is an AEAD cipher suite that uses the ChaCha20 stream cipher for encryption (instead of AES) and the Poly1305 MAC for authentication. It emerged from the need for a fast cipher on platforms where AES hardware might not be available (e.g. mobile devices). Google and the IETF championed ChaCha20-Poly1305 for use in TLS 1.2/1.3 and QUIC. It provides similar security guarantees to AES-GCM (confidentiality + integrity) but uses a different underlying primitive. Performance-wise, ChaCha20 can be faster than AES on systems without AES acceleration, and it has no known weaknesses when used properly. From a CISSP perspective, you should know ChaCha20 as a modern stream cipher (a redesign of earlier Salsa20), and Poly1305 as a MAC; together they form an AEAD used in TLS 1.3. Since CISSP focuses on principles, it’s unlikely to quiz you on specifics of ChaCha20’s rounds or Poly1305’s math. But it may appear as an answer option in a question about modern encryption for mobile/web (e.g., “What encryption algorithm is used as an alternative to AES in some modern protocols?”). In summary, ChaCha20-Poly1305 is a contemporary standard for authenticated encryption (RFC 8439), but it’s not a block cipher mode of AES – it’s an alternative symmetric cipher scheme altogether. Keep in mind that ChaCha20-Poly1305 is not (yet) FIPS-approved (as of 2025, NIST has not standardized ChaCha20 in FIPS, so it’s used in open protocols but not in environments that strictly require FIPS 140-validated algorithms). This might be worth noting if discussing compliance.

Relevance to CISSP Exam: The CISSP exam tends to emphasize widely adopted and foundational concepts. ECB, CBC, CTR, and GCM are definitely within scope as they are classic modes (and GCM is heavily used now). OCB and ChaCha20-Poly1305 are generally beyond what CISSP expects in detail, but knowing them can’t hurt. It’s safe to assume CISSP won’t dive deep into OCB’s operation or ChaCha’s design, but might mention them in passing or as distractors. For instance, a question might ask “Which of the following is an authenticated encryption mode?” with GCM, CBC, ECB, OCB as options – a savvy candidate would pick GCM (as the more commonly expected answer), although OCB is also one, it’s far less likely the test expects you to know OCB. Similarly, ChaCha20-Poly1305 could be referenced as an example of an AEAD cipher used in TLS 1.3, contrasting with AES-GCM. If you encounter it, just recall: it’s an AEAD cipher suite (stream cipher + MAC), not an AES mode. In summary, focus your studies on the primary modes (ECB, CBC, CTR, GCM) which cover the essential concepts of block cipher operation, and be generally aware that newer solutions like OCB and ChaCha20-Poly1305 exist and offer high performance authenticated encryption (likely adopted in specialized or modern scenarios, but not the core of CISSP crypto knowledge).

Conclusion and Security Best Practices

Implementing encryption is not just about choosing a strong cipher like AES, but also about choosing a secure mode of operation and using it correctly. As we’ve seen: – ECB mode is deterministic and reveals patterns – avoid it for any sensitive or repetitive data.

– CBC mode was a staple for years; it hides patterns but needs careful IV management and is vulnerable to padding oracle and tampering without an integrity check. If using CBC, always use unpredictable IVs and combine with a MAC (or use an AES-based AEAD like CCM).

– CTR mode turns AES into a stream cipher, offering high performance and simplicity, but never reuse a nonce with the same key or the cipher is broken. Also remember to authenticate the data since CTR alone doesn’t protect integrity.

– GCM mode (and other AEADs) provide a robust solution – they ensure confidentiality and integrity together. GCM is highly recommended in modern designs (and mandated by many standards) so long as you manage the IVs properly (unique per key). It eliminates whole classes of attacks (padding oracles, message forgeries) that plagued earlier modes.

– Key management is equally critical across all modes: use strong keys (per NIST guidelines, at least 128-bit for symmetric), rotate keys periodically if needed (especially if encrypting very large volumes with one key), and store/handle keys securely. Modes like CTR/GCM also impose limits on how much data can be safely encrypted per key (due to probability of IV collision or tag forgery) – for instance, NIST SP 800-38D suggests a maximum of 2^32 blocks (~68 billion blocks, or 4 petabytes with 128-bit blocks) per key for GCM to keep the chance of nonce repeat negligible.

– Standards compliance: NIST and ISO standards provide guidance to ensure implementations avoid pitfalls. Refer to NIST SP 800-38A for general mode requirements and NIST SP 800-38D for GCM specifics. Adhering to these recommendations (e.g. unpredictability of IVs, uniqueness of counters, using MACs or authenticated modes) will align your implementations with approved cryptographic practices. For CISSP and real-world alike, citing these standards shows due diligence.

In closing, a CISSP professional should be able to identify the appropriate mode for a scenario (e.g. fast streaming encryption – use CTR or GCM; need integrity – use GCM or add a MAC; legacy system – maybe CBC with HMAC; never ECB except perhaps in trick questions). You should also recognize the common vulnerabilities associated with each mode and how to mitigate them. By mastering block cipher modes from basic ECB to advanced GCM, and understanding the guidance of security standards, you’ll be equipped to design and assess cryptographic solutions that meet both the confidentiality and integrity requirements expected in the field and on the CISSP exam.

References

- Block Cipher Mode of Operation – Wikipedia

Comprehensive overview of block cipher modes, history, and operational concepts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation - NIST SP 800-38A – Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation

Official NIST guidance defining ECB, CBC, CFB, OFB, and CTR modes and their security requirements.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/legacy/sp/nistspecialpublication800-38a.pdf - NIST Proposal to Revise SP 800-38A (2022)

Discusses modern cryptographic risks, deprecating ECB, and promoting authenticated encryption. Includes references to BEAST, padding oracle attacks, and implementation flaws.

https://csrc.nist.gov/news/2022/proposal-to-revise-sp-800-38a - DestCert CISSP Guide – Types of Ciphers: ECB, CBC, OFB & More

CISSP-focused explanation of block cipher modes, including the ECB “penguin” illustration.

https://destcert.com/resources/types-of-ciphers/ - CVE-2017-5933 – Citrix NetScaler AES-GCM Nonce Reuse Vulnerability

Real-world example of nonce reuse breaking AES-GCM security guarantees.

https://www.cvedetails.com/cve/CVE-2017-5933/ - Galois/Counter Mode – Wikipedia

Technical explanation of AES-GCM, authenticated encryption, and parallelism.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galois/Counter_Mode - NIST SP 800-38D – Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) and GMAC

Authoritative NIST specification for AES-GCM, including IV uniqueness, tag generation, and limits.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/legacy/sp/nistspecialpublication800-38d.pdf - Reddit r/crypto – Discussion on NIST GCM Nonce Guidelines

Community discussion explaining reasoning behind strict IV requirements in AES-GCM.

https://www.reddit.com/r/crypto/comments/9jhysf/whats_the_reasoning_behind_nist_guidelines_on/ - Stack Overflow – AES-CBC vs AES-GCM IV Requirements

Practical explanation of why random IVs are acceptable for CBC but dangerous for GCM if reused.

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/36760973/why-is-random-iv-fine-for-aes-cbc-but-not-for-aes-gcm - Crypto StackExchange – AES-GCM Recommended IV Size

Explanation of why 96-bit (12-byte) IVs are recommended for AES-GCM.

https://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/41601/aes-gcm-recommended-iv-size-why-12-bytes - IETF RFC 5084 – Using AES-CCM and AES-GCM

Defines how authenticated encryption modes are used in secure network protocols.

https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5084 - ChaCha20-Poly1305 – Wikipedia

Overview of a modern AEAD cipher suite used in TLS 1.3 and QUIC.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ChaCha20-Poly1305

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.